The Update

The rules for the next American Guild of Organists National Competition in Organ Improvisation have been released and are available here. While the competition has not been without changes in the past, this set of rules is a significant departure from previous versions. Even if I thought changes in the rules were warranted, I’d like to make some observations about the new rule set that seem to run counter to the spirit of an improvisation competition.

Time lag

Most competitions begin with a recorded round, leading to a selection of semi-finalists who will compete live in person. A smaller number of finalists is then selected to compete in one last performance evaluation. When there are only 5-6 semi-finalists, most competitions hold the semi-finals and finals a few days apart from each other. For the 2016 edition of NCOI, the semi-finals will be held at the regional convention almost a full year before the finals. For a competition focusing on creating music with minimal preparation, having a year between rounds might as well be having two different competitions.

Repertoire

The 2016 NCOI adds a repertoire requirement. To win the competition, not only will one need to improvise, four substantial pieces of repertoire must be learned. To ask an improviser to demonstrate technical ability and mastery of the instrument by playing a piece of repertoire seems reasonable. I know there are other improvisation competitions that demand repertoire, but in no other case does the time for repertoire become more substantial than the time required for improvisation. In the NCOI semifinal round, it could take a competitor longer to play the repertoire requirement than to meet the improvisation requirement!

Hymns

The other new requirements for the 2016 edition are hymns and figured bass. While competitors have been provided hymn tunes as themes for many past competitions, it is now a requirement for a competitor to actually play a hymn with people singing. Recognizing that creating hymn introductions and varied accompaniments is a skill that at least some organists practice every week, this seems to be a more reasonable new territory for NCOI to include. However, as there was a separate hymn-playing competition held in Boston, it seems much preferable to me to continue holding a distinct hymn-playing competition rather than folding this skill into the improvisation competition. While related skills are involved, I would still consider improvising to accompany a congregation as a small subset of the skills necessary to win an improvisation prize.

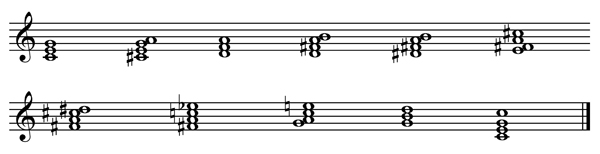

Figured Bass

While hymn playing may be the bread and butter of most organists’ playing duties, realizing a figured bass seems completely foreign to what most organists must do even occasionally. While improvisers may (should) learn to realize figured bass, it seems to me like asking the entrants in NYACOP to play scales and arpeggios for their assigned repertoire. Who would go to a performance competition to listen to scales and arpeggios or Hanon exercises? While I may be exaggerating slightly to make my point, if a candidate doesn’t know how to realize a figured bass, I feel pretty confident that they won’t be able to improvise variations on a given theme. I say don’t waste time asking for a figured bass, let’s hear the variations!

Preparation

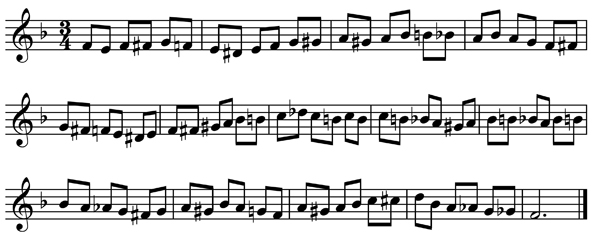

While the rules for the timing of the preliminary round need some further clarification (Does the competitor get three 30 minute preparations or only one?), the significant change in preparation time is the availability to use the organ and the material that is provided more than thirty minutes in advance. Granting access to an instrument during preparation time makes it easier for candidates to verify or practice ideas before performing, but is still a minor change compared to the release of themes days or months in advance. For the preliminary round, the competitor is to improvise five contrasting variations on Vom Himmel hoch. The theme is already known, so there is plenty of time for an enterprising composer to actually write a set of variations, memorize them, and then perform them for the recording. With a few months of preparation, I am sure that the quality of variations heard by the judges will be better than in previous years, but I have no confidence that they will be able to select the best improviser from an exercise with this much preparation time.

Likewise where the themes are given three days in advance for the semifinal and final rounds, I become less assured that what we hear will be an improvisation. Having written a Prelude and Fugue (albeit short) in less than a week and even some compositions in a few hours, I certainly could plan out very carefully if not outright compose my entry. Anyone with sufficient skills to win the competition could certainly posses the skills to compose a piece that fast and either memorize it or bring rough sketches to the competition.

To counteract these potential composition practices, there are very particular rules about what a competitor may write on a piece of paper and bring to the console for the competition. Certainly as long as themes are given out days in advance, what sort of papers one can bring to the competition should be restricted, but what does it mean to compose full harmonies? Would writing out figures over a bass line or using guitar/jazz chord notations be a rule violation? If the goal of all these changes is to raise the level of performances, why couldn’t the competitor take part of the thirty minutes of preparation time to write out harmonies in whatever format he or she chooses? Restricting the paper brought to the competition seems to be a much cleaner rule than trying to tell someone what can or cannot be written down.

Adjudication

Sadly, too few organists practice improvisation at the level where they could consider entering NCOI. It is a difficult skill to master, and even more difficult to teach. With only a handful of master improvisation teachers in this country, in order to avoid any potential conflict of interest where teachers judge their own students, many times the best improvisers are left out of the judges pool. Having a problem finding qualified judges however is not solved by adding more people to the panel. I propose following the model of St. Alban’s, Concours André Marchal, Chartres, and Haarlem where the jury is announced in advance. Competitors are hidden from the judges during all rounds of the competition and are free to study however often they can beforehand with the jury members. Having well-qualified jurors seems much preferable to me than having more people on the jury (especially if they cannot improvise).

Final Round

The AGO has a long tradition of offering certification to its membership. Perhaps unknowingly, the AGO has just set up three levels of improvisation certification corresponding to the preliminary, semifinal and final rounds of the NCOI. When viewed through the lens of certification, each of the requests at the different levels seems appropriately graded and a reasonable way to verify that someone has a well-rounded skill set. Just as a math teacher would ask a student to show his or her work to get to the final answer, it seems perfectly reasonable in a certification process to verify that a candidate can cover all the required bases. At a competition however, repeatedly asking a candidate to do the musical equivalent of reciting a multiplication table is redundant and distracting from the primary topic of improvisation.

Coda

I understand that there was an age limit proposed initially in the 2016 rules for NCOI. A competitor in the 2014 NCOI succeeded in getting that removed by appealing to the AGO’s purpose of professional development and the lack of entrants selected for the competition above that age limit. While I hope the committee will consider my viewpoint for further revisions to the 2016 rules, I have no expectations that any further changes will be implemented for this year. The best suggestion I can make for this rule set would be to expedite the process and hold the final round in Charlotte in 2015 a few days after the semifinal round. Launch a new set of rules for 2016 in Houston with a panel of three judges selected and announced in advance with performance requirements similar to NCOI 2014. Remove the hymn playing (and figured bass) requirements from NCOI and establish a regional hymn playing competition that requires improvised introductions and accompaniments. (The winners of this competition could then provide a fabulous hymn festival for the following national convention!) Finally establish procedures to offer one or more certificates in improvisation as outlined above.

As a devoted supporter of the art of improvisation at the organ, I wish to support any effort to encourage more people to improvise and to raise the level of improvisation in this country. (After all, I started organimprovisation.com in my free time.) I hope AGO will take my suggestions and turn NCOI back into a competition and begin to explore the certification and other hymn-playing competition ideas I have offered here so that we may all work together to encourage spontaneous music making.

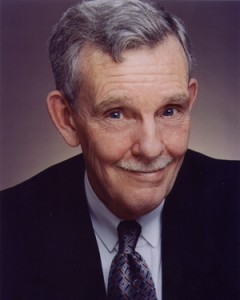

Glenn Osborne

www.wmglennosborne.com