One of the skills every improviser needs to have in their toolbox is the ability to transpose. Any of the larger forms which include a development section require the repetition of material in different keys. While it is acceptable to modify the material in the development, the best preparation for that is to practice strict transposition.

There are three ways that can learn to transpose: by ear, by clef, or by analysis. Some experience with all three can be useful as improvisers.

Using Your Ear

The ear is a great asset in transposition. It will be how you check if the notes you play sound the same in the different keys. If you have learned a melody by ear, then it may be easy to transpose by ear. Harmonies, especially complex ones, can by much harder to transpose by ear. This can be the slowest way to practice your transposition, but the ear will always be how we judge if our transposition is correct.

Using a Clef

The simplest transpositions are those by a half-step. Depending upon how many accidentals are in the piece, it is relatively easy to move a piece from Ab major to A major by simply changing the key signature. Likewise, moving down from E major to Eb major requires only a change in key signature and some attention to the alterations.

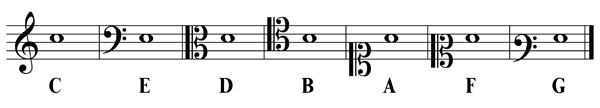

It is also possible to change the clef and read the music in a key further away. Sadly, most musicians today are generally only fluent in reading treble and bass clef. Violists will know alto clef. Some trombone and cello players will know tenor clef, but unless you read from a lot of early music scores, you probably haven’t spent much time with the other C and F clefs. There are enough different clefs that any note on the staff can actually be any pitch. Here’s an example of the same space on a staff and how it appears with the different clefs:

The way I learned to read these clefs was with Preparatory Exercises in Score Reading by by R.O. Morris and Howard Ferguson. (This is an Amazon affiliate link.) I spent one summer working through learning to read the various C-clefs and larger open scores. Being comfortable reading the different clefs makes it much easier to transpose pieces into more distant keys. I strongly encourage you to master as many clefs as you can.

Transposition by Analysis

Learning to read by clef reinforces reading by interval. One form of transposition would be to consider the interval that each voice moves. This can be very helpful when transposing a single melody or theme but also for complex harmonic structures. Recognizing that the alto moves a half-step down might be easier to see than reading the part in a new clef which shows a movement from F# to E#. In a tonal piece where you can analyze harmonic function, knowing that the original is a ii-V-I progression should make it easier to play the proper notes and progression in the new key.

One of the exercises I did daily for almost 6 months was to play a single Bach chorale in all twelve keys. Not only did this help me recognize standard chord progressions and voicings, I played everyday in keys that most people avoid, e.g. Eb minor, Bb minor, and F# major. I now read harmonic function almost as fast as I read the notes on the clef. The further I have to transpose a piece, the more likely I am to rely upon some form of analysis in addition to using a clef and my ear.

Applications

I still remember my amazement when one of my theory (and piano) teachers told me that Alfred Cortot suggested transposing Chopin etudes into different keys while keeping the same fingerings! I left my piano studies behind well before I ever played any Chopin etudes, however as an aid towards improvisation, I would recommend transposing repertoire. Let’s take something a little easier like the first of Louis Vierne’s 24 Pièces en style libre, the Préambule. (Free score available through IMSLP.)

The simple texture of this piece makes it relatively easy to transpose by ear or clef. The harmonic passages on the Récit will require some analysis (harmonic or melodic) in order to master. For my own practice, I read through the piece quickly in several keys:

There are also complete performances of the original C Major, and transpositions to C# major, D Major and Eb Major.

Once you’ve transposed a piece like this, use it as a model for improvising. Follow the score, keeping the same registrations and rhythms, but change the notes. After playing the piece in several keys, I improvised an imitation Vierne piece in F Major and in G minor. There are some hesitations as I searched for similar interesting tonal gestures without following exactly what Vierne did, but that’s why we practice. I decided to make this exercise my prelude this weekend, so there are two more that follow the score less slavishly in A minor and D minor as well.

Practice

Transposition is a skill that everyone easily recognizes as something that must be practiced in order to be mastered. Improvisation requires practice as well. Whether you choose a piece by Vierne or another favorite composer, I hope you will spend some time practicing it transposed and then imitating it in improvisation.

Glenn

Newsletter Issue 61 – 2016 10 03

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.

![vierne[1]](http://www.organimprovisation.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/vierne1-300x194.jpg)