Structurally, a French Classical Récit may not seem too difficult to improvise. Pull out a solo stop and a bourdon (maybe with a montre 8′ or flute 4′). Play for a couple of minutes. Make sure you cadence in the same key you started, and you’re done. Easy, right?

Maybe so. Maybe not.

At first glance, Récits come with a variety of registrations: cornet, cromorne, trompette, nazard, tierce, hautbois, and even voix humaine. There are even movements that dialogue between two different solo registrations so that you don’t even have to limit your selection to one at a time! While many of these movements are in some form of 4/4 time, pieces with three beats per measure are not uncommon. Aside from an occasional suggestion of some snippet of a phrase from the chant, there is usually not a distinctive melodic motif or other form expected for the piece. With so many options, what makes it so difficult to be authentically French Classical?

Unwritten Expectations

About twenty years ago, I came across an article that delivered an a-ha moment for me about improvisation and also prepared me to study abroad. Unfortunately, I have no idea who the author was or where the article appeared. (Presumably the photocopy I made of it might be hiding in an unopened box from my recent move, but was likely misplaced many years ago.) The article compared improvising to learning the unwritten rules of a culture. Every culture has and teaches its members a certain set of behavior an knowledge. Most people do not realize the extent of this cultural formation until they encounter a radically different culture while traveling.

While it is easy to accept and understand that each culture teaches its members its own set of knowledge and behavior, the revelation for me in this article was that the level of assumed knowledge varies from culture to culture. The author compared the cultures of Germany, France, the United States, and Japan. Germany demonstrated the lowest level of assumed knowledge. Germans will explain what you need to know to you clearly. If the information is important for your understanding, it will be included and explained by a German.

Moving to a slightly higher level of presumed knowledge are the residents of the US. (I’ll call us Americans for brevity even though I recognize there are many others on this continent that can use that title and not be the group the author referred to.) As an American, I am likely to presume that my audience has some familiarity with the topic I am presenting. Ask questions, and I’ll fill in any details you need, but I’m not going to bore you with details that you may already know if I can make my point without them.

in France, a great deal more knowledge is presumed. Where an American might presume you’ve heard of an author before, the French will not only expect you to know who the author is but also when he lived, what he wrote, and something about his style or why he was influential. I was very thankful to have learned this before I went to study in France. In a practical example, if I hadn’t known there was a discounted train ticket price for students, I would have never been told or offered one by the sales agent. Presumed knowledge is not explained.

The culture with the highest level of presumed knowledge in the article was Japan. I have never traveled to Asia, so cannot verify how different this is from the other three cultures (which I have experienced). I do know there are many more cultural rules and behavioral expectations in Japan, so this hierarchy of assumed knowledge seems to make sense to me. Neither the author of the article nor I imply that any of these cultures is better than the other. They are simply descriptions that are useful to know, especially when moving from one culture to another.

From Culture to Music

Music is often called a language, so carries it’s own set of implied knowledge and structure. The French presume a certain level of knowledge that remains unstated. The title of a movement not only gives the registration, but so far has also implied a tempo and character. It’s no surprise then to discover that Récits have different characters and compositional styles based upon the solo voice chosen. If more than one option is given by the composer for the solo voice, then it is expected that the tempo and ornamentation of the piece will change with the registration.

Here are some of the differences between the different solo stop pieces:

Récits de Cornet, Tierce and Nazard

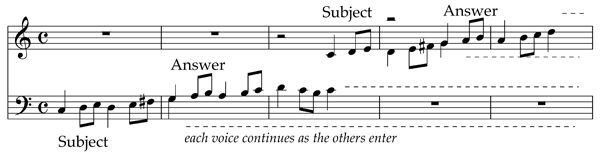

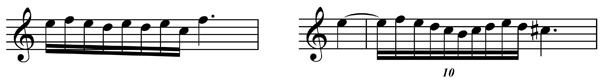

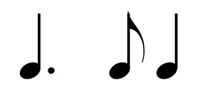

The Récits de Cornet are the quickest of these solo movements. Ornamentation is very florid with irregular groupings of notes (5, 9, or even 10) very common. For example:

Slightly slower than the Récit de Cornet, but still generally a lively piece the Récit de Tierce often ends with two upper solo voices. The Récit de Nazard is the slowest of these three, generally marked Largo, Andante or Tendrement (Tenderly). Clérambault is the exception with a Récit de Nazard marked Gayment et gracieusement.

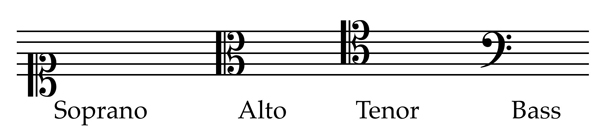

Récits de Trompette, Cromorne, Hautbois and Voix Humaine

Sometimes called a Dessus de Trompette because the trompette is used in the upper voice (as opposed to a Basse de trompette), these are the most lively of the reed solo movements. The solo writing often imitates gestures played by a real trumpet, with lots of skips between notes of the same chord:

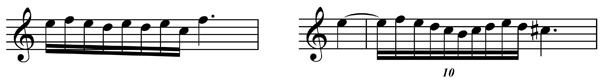

By contrast, the Récits de Cromorne are much slower and more melodic, imitating a singer:

The Hautbois being a later innovation to the French Classical organ, these récits are generally quicker and more active than a récit de cromorne. They are modeled more after writing for the violin than purely vocal styles. Finally, the Voix humaine is the slowest of the récits, played in a more legato, vocal style, reflecting the name of the stop.

Immersion

The best way to speak a foreign language is to live in the country where you are completely immersed in the language and culture. Learning to improvise in French Classical style requires the same immersion with the native speakers. Just as there are accents and dialects in a spoken language, each composer will write a little differently than the next, but they will still speak the same language. Exposure and focused study will allow you to notice the unwritten expectations of the style like the differences in tempo and ornamentation between solo stops.

What musical elements have you learned through immersion? How long were you immersed before the knowledge appeared? How did you become immersed in a particular musical idiom? We have so many different musical styles available to us now, I believe it is more difficult to truly be immersed in a musical language, but I’d love to hear any immersion stories you might have.

Hoping your Récits sound truly French!

Glenn

Newsletter Issue 46 – 2015 08 17

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.