Earlier this summer, I taught an organ masterclass at the National Pastoral Musicians convention in Cincinnati. Participants were encouraged to bring repertoire or ask questions about improvisation. One of the objectives of improvising can be to create a piece that sounds like it might be written down, so when the student was interested, we looked for improvisation skills to learn from the repertoire that we covered. One of the pieces presented then seemed like a great piece to share here, so let’s take a look at Johannes Brahms’ chorale prelude on “Schmücke dich, o liebe Seele.”

I recorded the video above earlier this spring at the Cathedral of Mary Our Queen. A basic harmonization of the chorale can be found in the Hymnal 1982 which was in the pews at Christ Church Cathedral where the masterclass was held. So with scores for the chorale and the prelude on the music rack, we pondered, how did Brahms get from one to the other?

Form

Any time you start an improvisation, it is helpful to know the form you intend to create. You may choose or need to deviate in the form after you start, but if you haven’t chosen a form to begin with, it’s highly unlikely your improvisation will sound like a written piece….

The chorale in the hymnal is in four-part harmony. Brahms provides no introduction, and leaves the melody in the soprano virtually unaltered. In this way, the melodic presentation and form of the two scores stay the same. The differences appear in texture, harmony, and figuration.

Texture

Brahms reduces the texture from four voices down to three. Because one of them as the melody is given to us, this actually makes our job as improvisers a little simpler. We only have to create two different parts to accompany the tune. If this seems difficult, we could even consider simplifying further so that we are only playing with two voices. One of the joys of improvising is being able to customize the level of difficulty. Unlike repertoire where we work to play what the composer has indicated, in improvisation, we can adjust to what we are able to manage.

Harmony

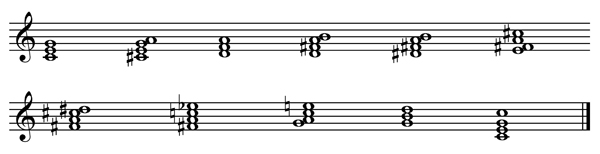

The standard harmonization of the chorale borrows from related keys only a small number of times. Brahms begins borrowing in the first full measure. The chorale only borrows from B major and F# minor. Brahms borrows from A major, C# minor, F# minor, and B major. He doesn’t just use secondary dominants for these keys. He even manages to include a D minor (sub-median, vi) for F# minor as he enriches the harmonic vocabulary. Brahms also occasionally fits two chords in the place of one from the chorale.

Figuration

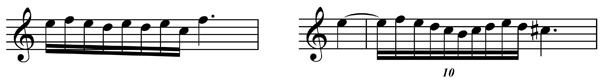

Finally, after the first two beats, Brahms manages to keep sixteenth note movement going throughout his chorale prelude. Neither the alto nor bass move consistently in sixteenth notes, but their combined movements provide continuous motion throughout the piece. He uses passing tones, arpeggios, neighbor notes, and suspensions all to help fill in this more active texture.

Sounds like Brahms

If we really want to sound like Brahms, we’ll need to look at more than just this one piece. However, as we compare the chorale to his chorale prelude, we can identify areas to study and develop in our improvisation tool box:

- How do you harmonize a melody in only three voices?

- What harmony can you imply with only two voices?

- Where can you borrow from related keys to make the harmony more rich?

- Where can you add additional harmonies to increase the frequency of changes?

- Where can you add passing tones, neighbor notes, or suspensions to make more active figuration in the accompaniment?

- What if you use triplets instead of eighth or sixteenth notes?

All of these are items that we can practice separately before combining them together. Work with them one at a time until you feel comfortable, then start combining them together. Brahms had a lifetime of experience before writing his chorale prelude. What will you be able to create if you continue practicing for the rest of your life?

Glenn

Newsletter Issue 65 – 2017 08 30

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.