As 2017 comes to a close, this question about ending a hymn seemed quite timely:

I’m looking for ways to creating a good last verse extravaganza of any hymn. I normally do the re-harmonization techniques. Apart from that, what other techniques can you suggest for me.

With Christmas services approaching quickly, I couldn’t help but look to two of my favorite last verses for inspiration. David Willcocks provides fabulous final verses for O Come All Ye Faithful and The First Nowell. What does he do in these two settings that we could apply to other tunes for a thrilling ending?

Start in Unison

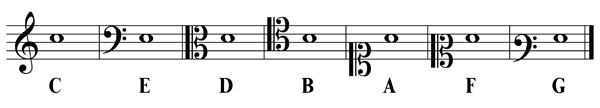

In the final verses by David Willcocks, he starts with the melody in octaves:

If you have a congregation that sings in harmony, this gives everyone an auditory signal to sing the melody. Unison singing is also typically louder than singing in parts. With a strong organ registration and strong unison singing from the congregation, this gets our final verse a solid start.

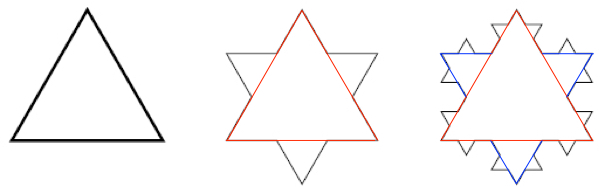

Pedal Point

In The First Nowell, David Willcocks moves quickly to using a pedal point after the unison beginning:

Pedal points build tension and anticipation by the changing harmonies above the anchor note. The best pedal points tend to be the dominant of the key. In The First Nowell, this is the A held through the entire second phrase of the hymn. For O Come All Ye Faithful, the pedal point doesn’t arrive until the refrain. The D (dominant of G) is held through the first two phrases of the refrain with a little rhythm to energize it when the melody phrases.

Descant

While it is possible to create some extravagant final verses through re-harmonization, there are virtually no accidentals in The First Nowell. While my first idea was to suggest using diminished seventh chords as in O Come All Ye Faithful, when I started comparing the two, I realized it was the descant above the melody that makes the final verse soar. Until the refrain of The First Nowell, there is no one singing a descant, but the organ abandons the melody and moves higher many times throughout the verse. The organ acquires its’ own melody which is quite singable. Here then is where our real improvisation practice begins. How many other melodies can you create while using the same harmonies as a given hymn tune? If you can do this while changing the harmony as well, you will be in good shape to create a true extravaganza for the last verse.

Updates

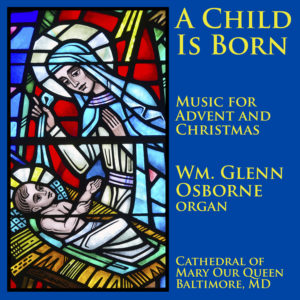

Earlier this month, I released my second recording from the Cathedral of Mary Our Queen: A Child Is Born. In addition to compositions for Advent and Christmas, it includes several improvisations. You can find it on iTunes, Amazon, and Spotify.

If you have been a long time subscriber, you may recall a short series of articles on modeling Tournemire. The Advent Suite included on the recording is a result of those newsletter issues. If you missed them, check out Issue 50, Issue 51, and Issue 52.

Wishing you all a Merry Christmas and Happy New Year!

Glenn

Newsletter Issue 70 – 2017 12 23

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.