Happy Easter! I hope all of you who had extra and important services over the last weeks are now recovered and ready to continue with your improvisation study. During this season with liturgical churches focus on the resurrection of Jesus Christ, it seemed fitting that I should resurrect the newsletter and take up the task once again of encouraging people to improvise at the organ. The message of Christianity has not spread far and wide because it was only practiced by a few people, but because those who practiced it told others about it. We must do the same for improvisation. If you have colleagues that do not improvise, teach them something simple as a way to get started (or send them to explore the previous newsletters).

Happy Easter! I hope all of you who had extra and important services over the last weeks are now recovered and ready to continue with your improvisation study. During this season with liturgical churches focus on the resurrection of Jesus Christ, it seemed fitting that I should resurrect the newsletter and take up the task once again of encouraging people to improvise at the organ. The message of Christianity has not spread far and wide because it was only practiced by a few people, but because those who practiced it told others about it. We must do the same for improvisation. If you have colleagues that do not improvise, teach them something simple as a way to get started (or send them to explore the previous newsletters).

Gradus Ad Parnassum

Aloysius– But are you not aware that this study is like an immense ocean, not to be exhausted even in the lifetime of a Nestor? You are indeed taking on a heavy task, a burden greater than Aetna.

My area of focus for 2016 is counterpoint. I was fortunate as an undergraduate student that my composition teacher included counterpoint exercises as part of every lesson. Most undergraduate theory programs include some study of harmony and counterpoint, but usually spend more time analyzing them than actually creating them. For me, this is the equivalent of learning to read, but never learning to write or speak. As improvisers, we need to learn to speak music, and thus have embarked upon the lifetime of learning Johann Joseph Fux mentions in the quote above.

Gradus Ad Parnassum is one of the classic texts for the study of counterpoint. Written in 1725 by Johann Joseph Fux, it was held in high esteem and used by such composers as Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, Brahms, and even Strauss. It is written as a dialogue between a student, Josephus, and the teacher, Aloysius, identified in the Foreward as Palestrina. The dialogue is a fictional creation of Fux therefore, but is meant to present the rules of counterpoint (indeed all musical composition) as practiced by Palestrina.

Species Counterpoint

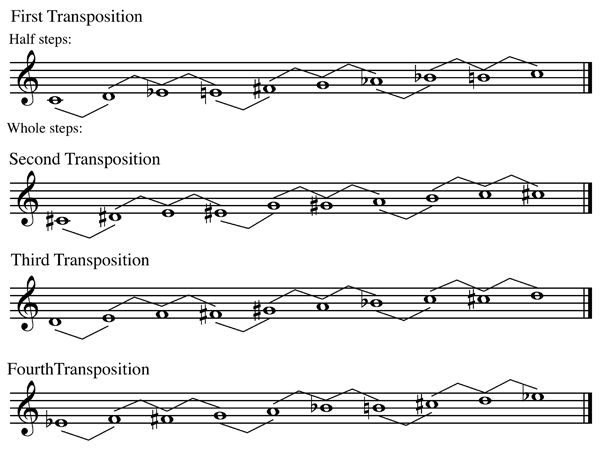

One of the advantages of learning composition through the study of counterpoint is the very easily identified and graded levels. Beginning with only two voices, the student progresses through five species before adding another voice:

- First Species – note against note

- Second Species – two notes against one

- Third Species – four notes against one

- Fourth Species – syncopation

- Fifth Species – florid counterpoint

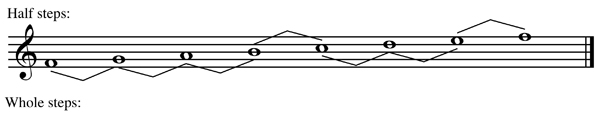

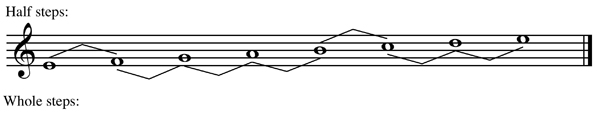

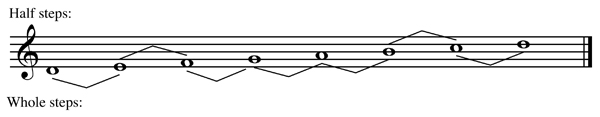

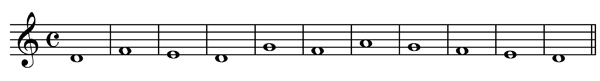

When creating counterpoint, one of the voices is identified as the cantus firmus. This is the given melody for the exercise that may not be changed. The other voice(s) must be written to follow the rules and fit correctly with the cantus firmus. Here is the first theme Fux provides:

All notes in first species counterpoint must be consonant intervals: 3rds, 5ths, 6ths, or octaves. There are many more rules regulating the movement between the voices, but before we get there, let’s consider some practice ideas we can take away from what we’ve covered so far.

- All rhythms are equal in first species. What happens to a melody or theme if we strip the rhythm away from it? Some hymns are almost all quarter notes, so won’t change much. Others have a variety of rhythms and will sound quite different when equalized.

- Counterpoint can appear either above or below the cantus firmus. Here is a chance to practice our dexterity at the organ. Each of your hands, as well as your feet could be the cantus firmus, while one of the others plays the counterpoint. For an added challenge, play the theme in the bass register with the right hand while your feet play an added melody above on a 4′ (or 2′) stop!

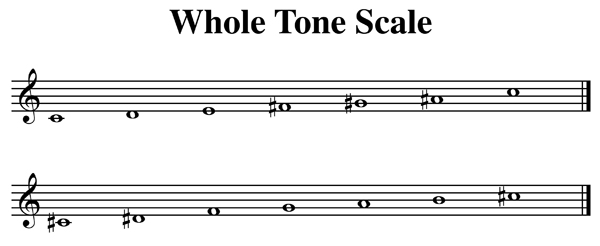

- Fux (and Palestrina) make use of the church modes: Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, and Mixolydian. If these modes are not part of your improvisational vocabulary, spend some time becoming more familiar with them. Ideas for practicing them can be found here and here. Counterpoint is not required in order to learn a mode.

- Themes are written in whole notes. Practice slowly. Whether it is counterpoint, or some other improvisation technique, take your time. Especially as we move into more complicated counterpoint, never play faster than you can think.

Spread the Word

Improvisation is not an easy task to master. It takes time and practice, but there are ways to start and make it accessible to everyone. In this Easter season when Jesus sent his disciples out to spread the Good News, I hope you will practice your improvisations and share with others the joy and delight you find in creating music in the moment.

Wishing you all the best,

Glenn

Newsletter Issue 56 – 2016 04 04

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.