Composers create music for many different reasons. Occasionally, they write pieces to demonstrate techniques for their students, either as examples of instrumental technique or compositional practices to master. The Orgelbüchlein of Johann Sebastian Bach is a fabulous place to look for simple chorale treatment ideas. L’Orgue Mystique by Charles Tournemire offers a wealth of ideas for how to work with chants. As improvisers (and composers) we need to spend some of our time studying the masters that came before us and learning to use the material (notes, harmonies, and sound colors) that we have available to us.

Paul Manz

One of the great American composers and hymn players of the twentieth century was Paul Manz. He produced countless volumes of pieces based upon familiar hymn tunes. Published with the title of Improvisations, many of these pieces could be models for us to follow, suggesting ideas and techniques for us to learn and apply to other melodies. One of his collections that I’ve had in my library for many years is his Improvisations for the Christmas Season, Set 1. It includes settings of the chorales Nun Komm der Heiden Heiland, Veni Emmanuel, and Wachet Auf along with a few others. Though the volume is labeled for the Christmas season, these are Advent chorales, so I typically will use them in the weeks leading up to Christmas. (That is, if I remember to take my score out of the file cabinet and bring it to church!)

Veni Emmanuel

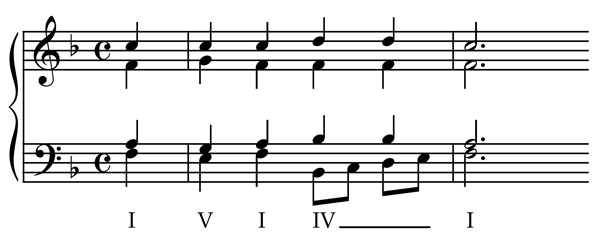

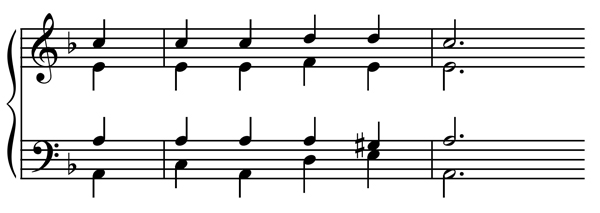

One of the settings in the collection that fascinated me was a very simple setting of O Come, O Come, Emmanuel. It is a short one page piece. The pedal part consists entirely of a single note, the tonic E. The melody is presented on a solo stop and the chordal accompaniment on a softer registration. I found a performance on YouTube that you may hear by following the link here. What fascinates me about this composition is how Manz begins and ends with cluster harmonies and triads from within the mode, but then ventures quite far afield in the middle, using chromaticism might otherwise be out of place in a modal piece.

When evaluating an improvisation (or composition), I like to fall back on the four C’s that I outlined in the first newsletter issues: competent, convincing, coherent, and colorful. The mixture of chromatic and modal harmonic language could make this Manz piece incoherent and perhaps not very competent either, yet our ears accept the chromaticism. Why?

Anchors

This improvisation gives our ears two anchors to hold on to: the pedal point and the melody. Being a familiar tune, the melody (as the loudest voice) clearly has the strongest pull for our ears. The pedal point also orients us just as the north pole orients a compass. Regardless of which way we may turn, the pedal will enable us to gain our bearings and return home again. The chromaticism also has a direction to it – the chords continue moving up – giving our ear an expected resolution to the dissonance as well. All these together combine to create the color of the piece, enabling it to be coherent, competent, and convincing, in spite of the rather simple and perhaps uninteresting ideas that are combined to make the composition.

Try it for yourself

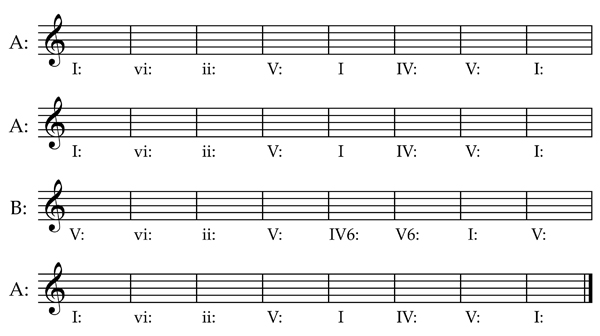

How can this piece serve as a model for us? What can we practice following this example?

While normally, pedal points can be boring and would often be discouraged, they can be useful in times of very chromatic movement. What sort of harmonic tension can you create over a pedal point? How long can you keep a listener’s attention with only one note in the pedal? Explore chromatic harmonies by changing one note at a time in the accompaniment. Does this work better with the melody in the soprano or tenor range? What difference does it make if the theme is in a major mode? What if the chromatic lines move down instead of up? Here’s a technical challenge for you: play the pedal point with the left (or right!) hand and the melody in the pedal. Choose different themes and try out all the different combinations of pedal point, melody and accompaniment that you can imagine!

May all your improvisations be competent, convincing, coherent and colorful!

Glenn

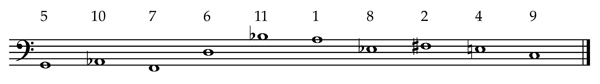

Recent additions to organimprovisation.com:

Themes:

Newsletter Issue 30 – 2014 12 01

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.