After a month of packing, moving and settling in to my new position at the Cathedral of Mary, Our Queen in Baltimore, I’m delighted to resume the regular weekly publication of thoughts and practice tips on organ improvisation. I’m still discovering the fabulous instrument at the Cathedral – stoplist available here – and look forward to posting videos later this year.

How Fast Can You Play

Back in October, I wrote an article on the first part of my first lesson with Franck Vaudray. At the time, I couldn’t find the paper that summarized my lesson and was my practice guide for the next week, but luckily while packing to move, I was able to locate it! So four months later, I’ll finally tell you about the second part of my lesson. (If you haven’t read the first part, it is available here.)

Melodic dictation

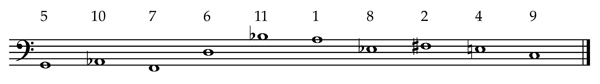

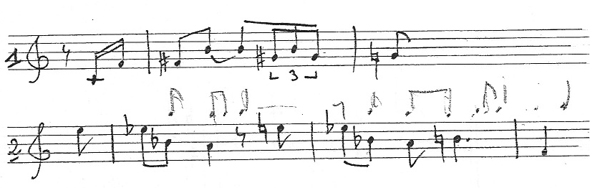

After assessing my technique and ability to play in an atonal style, this next part of my lesson tested my dictation and transposition skills and concluded with canons. Asking me to look away from the keyboard, Franck Vaudray proceeded to play a melody that I had to then play back to him. No reference or tonality was given. I had to find the right pitch and play the melody as he had just done. I don’t remember exactly how well I fared at this, but I do remember that Mr. Vaudray was kind enough to play the melody several times for me before I got it. We repeated the process for a second melody. Both are pictured below.

Transposition

Once I had the motives down, it was time to transpose them. If transposition is not something you practice regularly, I’d suggest moving up (or down) by half-steps through all twelve transpositions. Be sure and do this with both hands. As these motives are not exactly tonal, be sure and pay attention to the intervals and shapes as you practice the transpositions.

In my lesson, we may or may not have gone through all twelve transpositions of both melodies with both hands before we started a more advanced transposition cycle. Rather than simply move in one direction or even around the circle of fifths, I was asked to alternate hands with one hand moving higher with each transposition and one hand moving lower. Applying this to the first motif, the starting notes for this pattern look like this: (Stems up for the right hand, stems down for the left)

If you were mentally tired after the atonal lesson, this one really stretches the mind!

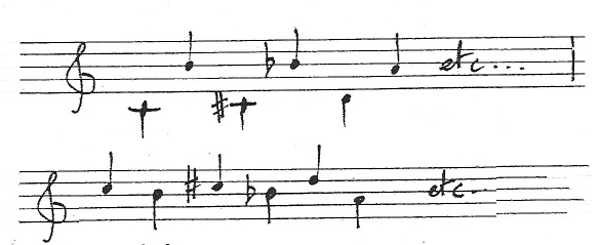

Canons

In the themes above, you may have noticed a rhythm written out above the second melody. This shows the rhythmic placement for that motive in canon. Not only was I asked to play the canon in any transposition, but eventually to play the canon in different transpositions. For example, the left hand plays as written while the right hand follows starting on G, a minor third above. While I don’t think I was asked to do this then, it would be an interesting exercise to try and play the canon following the transposition scheme above. That would be a real challenge!

Free at last

Finally, I was given free reign to improvise a piece using these motives. After transposing and playing them in canon for the past thirty minutes, it was relatively easy to keep the themes front and center regardless of the tonality that I might have wondered in to. I prepared a worksheet with the melodies and transposition scheme that you can download here for your own practice.

Thorough preparation

How much work do we do with a theme before we improvise with it? While not all forms or pieces would require the amount of preparation outlined here, is there a hymn or chant that you improvise on regularly? Will it work as a canon? Perhaps you should put it through the transposition and canon practice outlined here. The better we know the theme, the more flexible we can be in our improvisations, and the more competent, convincing and coherent they will be as well!

Wishing you all the best for 2015!

Glenn

Recent additions to organimprovisation.com:

Themes:

Newsletter Issue 32 – 2015 02 02

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.