As this issues is number twenty in the series of newsletters, I thought I’d offer a simple and practical list of twenty ways to practice a hymn that you can make part of your regular routine. Depending upon your experience level, some of these might be considered warm-up exercises while others will hopefully help you expand your improvisational toolbox. While I typically only give hymn melodies on the website here, I’m writing this list with the presumption that you have a four-part harmonization in front of you, so break open the hymnal and get started!

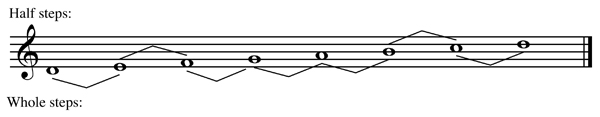

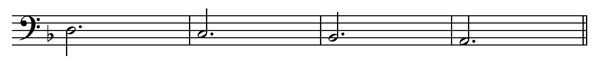

- Transpose the hymn to all the other major or minor keys.

- Play the hymn in other modes: change major to minor (or vice versa). Try Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, and Mixolydian (coming this Friday) as well.

- Invert the soprano and alto parts. (If this is your first effort at doing this, don't worry about parallel fifths for this or any of the other exercises on this list. Simply play the notes on the page.)

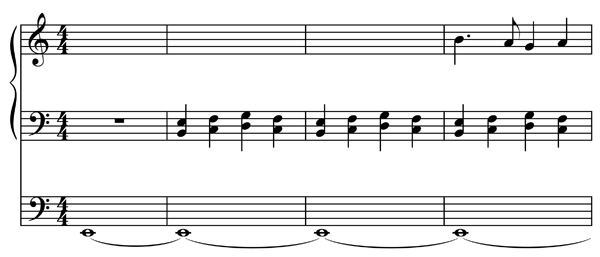

- Play the melody in the tenor (left hand) with the right hand playing the alto and tenor parts up an octave. Play the bass either with the left hand or pedals.

- Play the melody in the tenor(left hand) with the right hand playing the tenor part above the alto part. Again the bass can be played with the left hand or pedals.

- Use an 8' stop in the pedal to play the melody in the tenor register. Play the bass with the left hand while the right hand fills in from the tenor and alto parts.

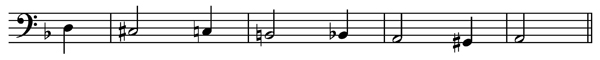

- Play through the hymn harmonizing each melody note as each of the following functions: tonic of a major chord, tonic of a minor chord, third of a major chord, third of a minor chord, fifth of a major chord, fifth of a minor chord, tonic of an augmented chord, tonic of a diminished seventh chord. (See Issue #7 for an example.)

- Rather than applying one type of chord throughout the entire hymn, choose a numeric sequence (such as 1-3-5, all in major) and follow the same idea as above. You could also follow a more complicated sequence, such as 1M-3m-5M-1m-3M-5m. While the progressions might not make much sense harmonically, this will help you think and shift between keys quicker.

- Play the melody as a two-voice canon at the distance of one note, a half-measure, and a full measure. Each of these canons can be practiced starting with the right hand, left hand or pedal creating six different combinations for each distance.

- Choosing the distance than works best, play through the canons again, but at different melodic intervals.

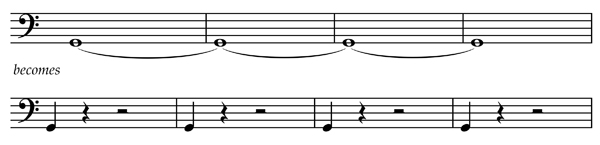

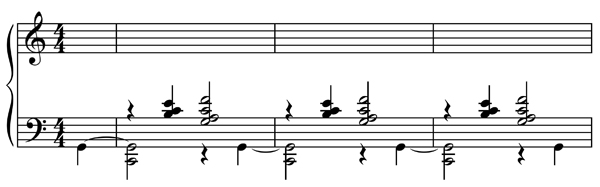

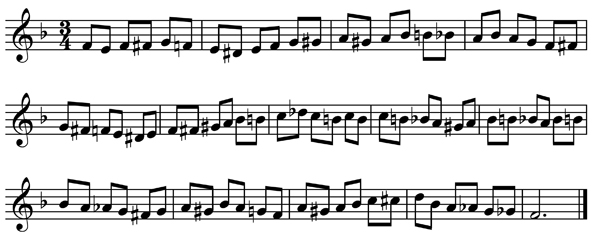

- Play a monophonic variation arpeggiating the chords in triplets or sixteenth notes. Be sure and try different figurations where the melody note is not always the first note of the arpeggio.

- Create a duo where the top voice is the melody and the bottom voice plays eighth notes (two notes for every melody note).

- Create a duo where the top voice is the melody and the bottom voice plays triplets (three notes for every melody note).

- Create a duo where the top voice is the melody and the bottom voice plays sixteenth notes (four to one).

- Repeat steps 12 to 14 with the melody in the lower voice and the more active voice above the melody.

- Repeat 12 to 14 but rather than ornament the bass, ornament the melody. Instead of a duo, you may choose to play the full ATB harmony as in the hymnal as the accompaniment.

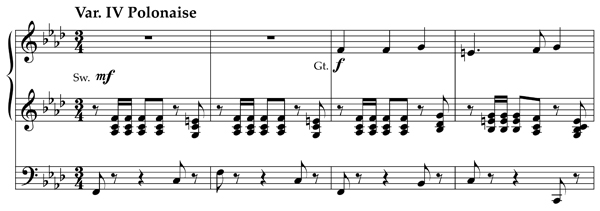

- Create echo passages by changing manuals (or registration) and repeating short sections of phrases, i.e. for a two-measure phrase, repeat the second measure, and then repeat the last half-measure again.

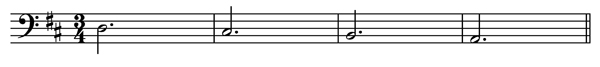

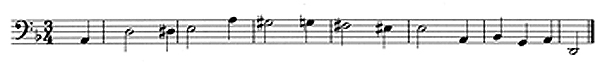

- Change the meter from duple to triple (or vice versa). How many different ways can you shift the meter? For example, one measure of four can become two measures of three or one measure of three.

- Change the meter to 5/4, 7/8 or some other odd (but consistent) meter.

- Improvise a toccata following the plan from the newsletter sign-up handout!

Many of these steps can be done at the piano and do not require a significant chunk of time, so I encourage you to practice as many of them as often as you can. If you can’t practice all twenty daily, choose as many as you can and practice them for twenty days and then move on to another set. Slowly over time, your improvisational skills will grow.

May your improvisations be better each day,

Glenn

Recent additions to organimprovisation.com:

Organists:

Mode:

Theme

Newsletter Issue 20 – 2014 09 15

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.