Jeffrey Brillhart

Breaking Free: Finding a Personal Voice for Improvisation through 20th Century French Improvisation Techniques. Published by Wayne Leupold Editions.

One of the great difficulties I see in the teaching of improvisation is choosing where to begin and how to cover the wealth of material that a well-trained improviser needs to know. Whereas Gerre Hancock focuses almost entirely on form throughout his book Improvising: How to Master the Art , the bulk of the material in Breaking Free concerns harmonic language.

, the bulk of the material in Breaking Free concerns harmonic language.

Jeffrey Brillhart attacks the challenge of what to cover and where to begin by narrowing the focus to “finding a personal language for organ improvisation through 20th century French Improvisation techniques,” the subtitle of the book. In the Introduction, Brillhart acknowledges that each student’s route to mastery is different:

There is no “one size fits all,” in learning to improvise or in teaching someone to improvise. What may work for one student may completely stymie another student.

…

Improvisation is a mystery. We do not fully understand what happens within the mind of the improviser while improvising. Improvisation is a search. It is a search for a personal musical language. It is a search for musical coherence. It is a search for personal self-expression. It is a search for beauty.

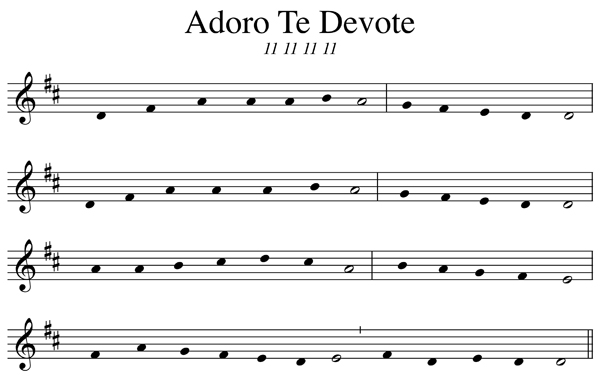

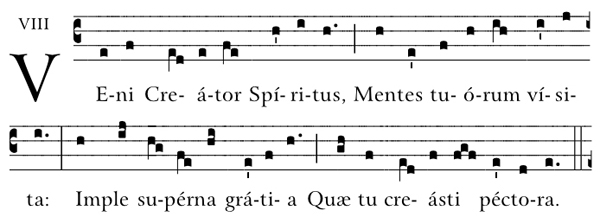

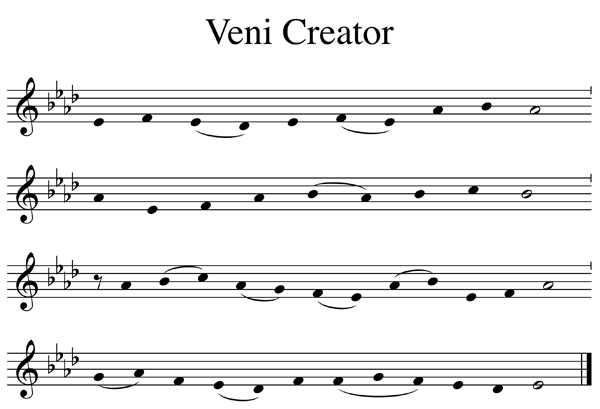

Breaking Free is a book filled with ideas for the student to explore. The first part (chapters 1-5) provides a philosophical grounding of improvisation and establishes the importance of the theme. Many example themes are given and chapter 4 is a catalog of development techniques. Any advice or examples provided are always accompanied by the encouragement of the student to find his or her own solution for how to treat the theme.

Part II (chapters 6-15) move into harmonic language and provides a framework not of scales, but intervals. Each chapter is devoted to a different interval (fifths, fourths, thirds, seconds, and so forth) and the harmonic colors that can be generated while using that specific interval to either harmonize or accompany the given theme. The pentatonic mode is also introduced and the student is urged to explore canons in this mode because of the harmonic simplicity the mode offers. Triads and seventh chords are also given their own chapters in this part, and while there may be references to key centers in the text, the student is encouraged to explore the textures without the restriction that a scale or specific mode would require.

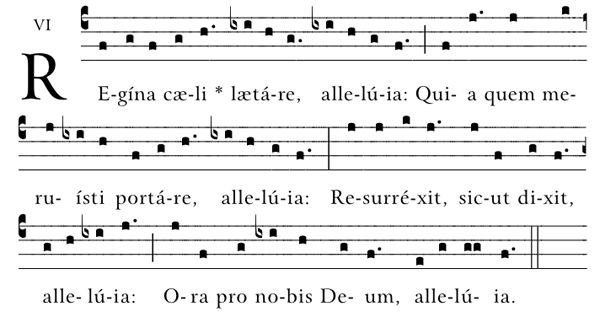

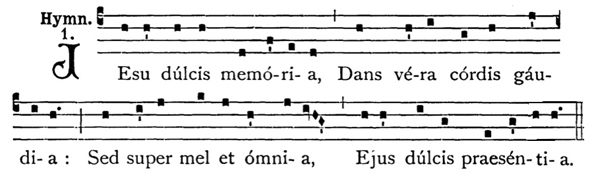

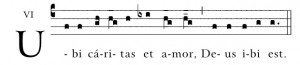

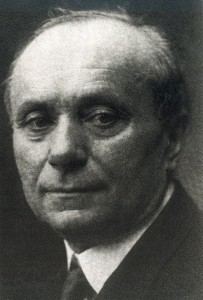

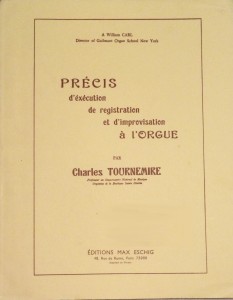

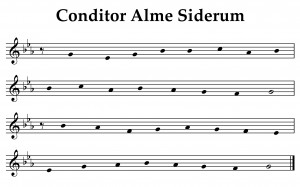

Part III (chapters 16-20) begins with a look at Charles Tournemire. This chapter combines the techniques already covered with the structure and style of a specific composer, and provides a bridge into a harmonic language built upon modes. The next three chapters explain and explore the modes of Gregorian chant, a common theme source for much of French music. The final chapter of this part looks at the Bartok mode and serves as a bridge into Part IV which covers the more complex modes of Olivier Messiaen.

Only in Part V (chapters 25-35) does Brillhart finally begin to address large scale forms. Forms covered in this part include Passacaglia, Song From, Scherzo, Sonata Allegro, the structures of Louis Vierne and Pierre Cochereau, free improvisation and finally improvising on a literary text. The last two chapters (Part VI) provide examples of the language of Debussy and Ravel for the student to explore. Finally, for the student still searching at the end of this book there is a wonderful two-page bibliography of high quality resources for further exploration either of improvisation or other specific musical topics such as harmony or counterpoint.

Having spent the majority of my formal instruction in improvisation learning from French teachers, I am delighted that Jeff Brillhart has created this volume. While it may not be exactly what I experienced in France, he provides a codified and logical progression for something that I saw many French teachers address in a very haphazard way. By choosing to focus on a specific style, he actually helps the student develop many tools that can be applied in other areas. The greatest difficulty with this book may come from the lack of specific challenges for the student. Each chapter of Improvising: How to Master the Art by Gerre Hancock concludes with specific activities for the student to complete before moving on. While each chapter in Breaking Free has numerous examples and may offer ways for the student to apply the materials in the chapter, there is no task given where the student (or teacher) can clearly know if they have understood and can apply the material presented. If the student is creative, then this is probably not much of a problem, but for a beginning improviser who has trouble generating ideas, this may make it difficult to use this book without the aid of a teacher. Perhaps unintended, but a likely benefit of a student working through this book will not only be a breaking free of harmonic language, but also a strengthening of the creative muscle.

by Gerre Hancock concludes with specific activities for the student to complete before moving on. While each chapter in Breaking Free has numerous examples and may offer ways for the student to apply the materials in the chapter, there is no task given where the student (or teacher) can clearly know if they have understood and can apply the material presented. If the student is creative, then this is probably not much of a problem, but for a beginning improviser who has trouble generating ideas, this may make it difficult to use this book without the aid of a teacher. Perhaps unintended, but a likely benefit of a student working through this book will not only be a breaking free of harmonic language, but also a strengthening of the creative muscle.

It takes a lot of varied skills to master the art of improvisation. Breaking Free by Jeff Brillhart is an excellent resource for adding tools to the improviser’s toolbox. Using this book, not only will the student break free harmonically, but he or she will also break free from the reliance on a teacher and discover his or her own creative potential. For anyone interested in improvising in a modern style (whether French or not), I highly recommend this book.